NNAI Livescu sponsors undergraduate research projects on various topics, overseen by faculty and staff in the initiative.

By Isabella Yuan, UCLA Human Biology and Society Major and Philosophy Minor

AI, Copyright Law, and Work-Made-For-Hire

I. INTRODUCTION

On November 3, 2018, computer scientist and inventor Stephen Thaler filed an application with the United States Copyright Office (USCO) to register a copyright claim on a two-dimensional artwork titled “A Recent Entrance to Paradise” (“Recent Entrance”). In the application, Thaler claimed that a machine learning system named the “Creativity Machine” had autonomously generated the artwork. For this reason, Thaler listed the Creativity Machine as the sole author of the artwork.

Thaler’s application was ultimately rejected by the USCO, which cited its policy that to be eligible for copyright registration, a work must be authored in the first instance by a human being [1,2]. While Thaler’s attempt to register the Creativity Machine as an author in a copyright claim was ultimately unsuccessful, it has prompted questions regarding the possibility of copyrighting works created exclusively with artificial intelligence (AI).

Driven by analysis of Thaler’s unsuccessful case in favor of extending copyright protection to autonomous AI-generated works, this primer addresses three core questions:

- Is AI-generated work copyrightable?

- How might AI-generated work become eligible for copyright protection?

- Should AI-generated work be copyrightable?

This primer determines that while autonomous AI-generated works are not copyrightable under current U.S. copyright law, the language of the Constitution leaves open the possibility of extending copyright protection to AI-generated works. Nonetheless, this primer concludes that copyright protection should not be extended to AI-generated works as doing so would undermine the original purpose of copyright to incentivize human creativity.

II. BACKGROUND

Copyright is the term for the legal protection of the property rights of one who creates original works of authorship that are fixed in any tangible medium of expression [3].The holder of a copyright has the exclusive right to reproduce, distribute, perform, display, or prepare derivative works based on the copyrighted work [4]. The USCO, a department within the Library of Congress, is responsible for administering U.S. copyright law. Its duties include registering copyright claims, maintaining public records of copyright claims, and developing regulations concerning copyright law [5].

U.S. copyright law is grounded in the U.S. Constitution’s Intellectual Property Clause, which gives Congress the authority to enact laws that “promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries [6]. The use of the term “author” in the Intellectual Property Clause has formed the basis of subsequent analysis and interpretations of ownership in copyright law.

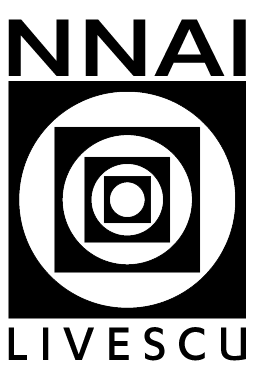

Currently, U.S. copyright law is primarily governed by the Copyright Act of 1976. According to the language of the Act, the author is generally the owner of the copyright except in specific cases, such as when the author assigns the copyright to another party, or when the author creates the work under a work-made-for-hire (WMFH) arrangement––when the work is created by an employee within the scope of their employment or when the work is specially commissioned under a written agreement [7]. According to the WMFH doctrine, the employer or commissioning party is considered the legal author and copyright holder of the work.

III. IS AI-GENERATED WORK COPYRIGHTABLE?

After Thaler’s application to register a copyright claim for “Recent Entrance” was denied, he filed a lawsuit against the USCO and its director, Shira Perlmutter [8]. As the only high-profile legal attempt to secure copyright protection for a work generated entirely and autonomously by an AI system, the Thaler v. Perlmutter case provides the current legal precedent for whether autonomous AI-generated works are copyrightable. Evaluating the arguments and rulings in thiscase can clarify how current legal standards interpret authorship and creativity as applied to AI-generated works.

In the lawsuit, Thaler contested the USCO’s requirement that the author of a work be human for the work to be eligible for copyright protection, making the argument that the Copyright Act does not explicitly define an “author” to be human and that the human-authorship requirement is unconstitutional and unsupported by case law [9]. Additionally, Thaler argued that he qualified as the legal author of “Recent Entrance” through the WMFH doctrine, claiming that the Creativity Machine functionally acted as his employee in generating the artwork.

The WMFH doctrine allows non-human entities like corporations to be considered legal authors despite not being natural persons. For example, Microsoft holds copyrights to software developed by its employees as part of their employment. The corporation is thus considered the legal author, even though the actual creator may be an individual employee. Thaler essentially argued that, as the owner and developer of the Creativity Machine, “Recent Entrance” was generated within the scope of a relation analogous to employment. He concluded that, pursuant to the WMFH doctrine, the resulting output should be attributed to him as the legal author.

The Court affirmed the USCO’s decision to deny Thaler’s application. In a Memorandum Opinion, Judge Howell addressed Thaler’s first argument––that the Copyright Act does not explicitly require that an “author” be human––by first conceding that the term “author” is undefined in the statute and that the definition of “author” has historically evolved in response to technological advances [10]. As an example, Judge Howell cited Burrow-Giles Lithographic Co. v. Sarony (1884), in which the Supreme Court ruled that the term “author” could extend to a photographer because the photograph was understood to represent the “original intellectual conceptions of the author [11].

Despite acknowledging that the definition of “author” has historically evolved alongside technological advances, Judge Howell held in granting summary judgment against Thaler that the understanding that the legal author must be human is based on long-standing precedent [12]. Judge Howell also emphasized that copyright law was designed to incentivize human intellectual labor, and that non-human entities like AI do not require or respond to such incentives [13]. Based on this conclusion that human authorship is required for copyright protection under the Copyright Act, Judge Howell rejected Thaler’s second argument––that he qualified as legal author through the WMFH doctrine––pointing out that because the work itself was not created by a human, it could not constitute a copyrightable work [14]. As a result, Thaler still would not qualify as the legal author.

Thaler then appealed this decision in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia, which affirmed Judge Howell’s decision to uphold the USCO’s decision to deny registration of the copyright claim for “Recent Entrance” [15]. In the Opinion, Judge Millett, writing without dissents or concurrences, followed the rule that human authorship is a prerequisite for copyright protection, adding that the Copyright Act makes sense only if the term “author” is understood to mean a human author [16]. Judge Millett also elaborated that the human authorship requirement does not call for a universal denial of copyright protection for works involving AI, noting that, depending on the situation, the USCO had previously approved registrations for works where human authors made use of AI [17]. For example, if a human has significantly modified AI-generated material in a sufficiently creative way, the work may be eligible for copyright protection. However, in such a case, only the modifications made by the human would be protected, not the AI-generated material itself [18].

According to Judge Millett, the main problem with Thaler’s application was Thaler’s admission that the work had been created entirely by the Creativity Machine without any human input. Thaler’s WMFH argument would have succeeded if a human creator was the actual author of the work and created it under a WMFH framework. Since that was not the case––the work was (according to Thaler) created entirely and autonomously by AI––there was no authorship to attribute, and Thaler could not be considered the author under the statute.

The Court of Appeals decision in the Thaler v. Perlmutter case was decided in March 2025. Rehearing was denied in May 2025 [19]. The holding that purely AI-generated works are not eligible for copyright protection under U.S. copyright law has not been challenged in court since.

IV. HOW MIGHT AI-GENERATED WORK BECOME ELIGIBLE FOR COPYRIGHT PROTECTION?

Though Thaler was ultimately unsuccessful in registering a copyright claim for an AI-generated work, his case raised interesting implications regarding legal authorship and legal personhood. While the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia and the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia both affirmed the USCO’s decision, Thaler’s point that the Constitution does not explicitly require that an “author” be human is correct. It is still plausible (though unlikely) that the USCO may revise its guidelines to allow for copyright registration of AI-generated works, or that a court may rule that human authorship is not necessary for copyright registration under the Copyright Act. As it is still possible for future legal developments to expand the definition of legal authorship to include AI-generated works, it is worth considering how current legal frameworks could accommodate such works if the human authorship requirement were lifted.

Before determining whether current U.S. copyright law can accommodate AI-generated works, it should first be determined whether AI is actually capable of creating “original” works in the sense required by copyright law. Before 1991, lower courts adopted a “sweat of the brow” or “industrious collection” test, by which compilations could qualify for protection as long as they demonstrated that substantial effort was put into creating them [20]. In Feist Publications, Inc. v. Rural Telephone Service Co. (1991), the Supreme Court held that the “sweat of the brow” doctrine was incompatible with the Constitution and that to be eligible for copyright protection, a work must have a “modicum of creativity” [21]. The Feist case marked a landmark shift from granting copyright based on the process with which a work is created to granting copyright based on the originality of the work itself.

The issue then is whether AI is capable of exhibiting a minimal degree of creativity when generating works. On the one hand, weaker AI such as large language models (LLMs) or image generators are trained on large datasets to recognize patterns and generate outputs based on statistical correlations rather than genuine understanding. These types of AI lack intention; they function more as tools than as independent agents. As a result, LLM outputs do not fulfill the “modicum of creativity” requirement since they, like the compilations in the Feist case, involve the arrangement of preexisting information based on systematic processes instead of creative choices.

On the other hand, stronger AI systems––particularly the hypothetical artificial general intelligence (AGI), which would possess human-like cognitive capabilities––could potentially generate entirely original works in the sense required by copyright law if they demonstrate intention in generating their outputs. As established in the Feist decision, copyright protection requires more than outputs derived from statistical correlations; it requires a minimal level of creativity that reflects independent intellectual activity. If stronger AI is demonstrated to be capable of ingenuity, its works would have potential to fulfill the “modicum of creativity” requirement. However, just simulating human cognition does not guarantee that stronger AI systems would exhibit genuine intention. Therefore, the eligibility of strong AI-generated works for copyright protection remains uncertain; strong AI may have the potential to meet the required threshold one day, but only if future developments demonstrate that it is capable of intention and ingenuity.

Having established that strong AI, but not weak AI, has the potential to fulfill the “modicum of creativity” requirement, it is worth considering how works generated by strong AI might qualify for copyright protection under current copyright law. As argued by Thaler, one path to eligibility could be under the WMFH doctrine, by which the employer is considered the legal author of any eligible works produced by an employee within the scope of their employment [22]. Thaler’s WMFH argument failed not only because of the human-authorship requirement but also because he could not demonstrate that (i) the Creativity Machine qualified as an employee within existing legal definitions, and (ii) the relationship between him, as the purported employer, and the Creativity Machine, as the purported employee, constituted a valid employer-employee relationship[23]. These limitations stemmed from the fact that, under current law, AI systems are not recognized as legal persons capable of entering employment relationships.

Based on the shortcomings of Thaler’s argument, one way for AI-generated works to become eligible for copyright by the WMFH doctrine is to have AI recognized as a legal entity. This would involve granting the AI some form of legal personhood––a status granted by law to an entity that allows it to have rights and obligations like a human being [24]. The primary example of attributing personhood status to non-human entities is the concept of corporate personhood, through which corporations are able to sue, be sued, own property, enter into contracts, and much more despite lacking human consciousness or other markers of personhood. Considering that the legal system already recognizes non-human entities like corporations as legal persons, it is plausible that AI could similarly be recognized as a legal entity one day. Recognizing AI as a legal entity would thus align with existing precedent of assigning legal personhood to non-human entities in certain respects.

One might argue that just because a non-human entity like a corporation can have legal personhood does not mean that AI should be granted the same. Their situations are not entirely analogous. After all, corporations can be seen as collections of human stakeholders, and their legal personhood can be seen as deriving from the rights and responsibilities of the humans who comprise them [25]. The same cannot be said of autonomous AI systems, which are not sentient and would thus lack intent and accountability in a way that a corporation (or a corporation’s constituents) would not.

That said, corporate personhood does not hinge on continuous human involvement. For example, decentralized autonomous organizations (DAOs) are blockchain-based entities that embed AI and automation into their operations and corporate structure extensively, such that they can operate with minimal human intervention [26]. In 2021, Wyoming became the first state to recognize DAOs as a form of Limited Liability Company (LLC). Tennessee and Vermont have since recognized DAOs as legal business entities, granting them legal status as well. DAOs involve humans to a similar extent that strong AI systems involve humans: both are initiated by humans but can operate independently. While the personhood might originally derive from the humans that create or maintain the DAO, the DAO can still hold legal personhood while operating autonomously without continuous human intervention. This suggests that autonomous systems, even those that are not human and are not continuously directed by humans, can still hold some form of legal personhood. Since holding legal personhood is not contingent on continuous human involvement, strong AI could potentially be granted legal personhood. Therefore, as long as it is capable of intention and ingenuity, strong AI could be granted legal personhood and could potentially (i) qualify as an employee and (ii) enter into a valid employment relationship, fulfilling the prerequisites of Thaler’s WMFH argument.

Even if (i) and (ii) were fulfilled, however, it is unlikely that the WMFH doctrine in particular would be applied to extend copyright protection to AI-generated works because AI does not fit neatly into existing understanding of an employee in labor law (hence the need to grant it some form of legal personhood in order for it to fulfill the WMFH doctrine.) It is more likely that the courts or the legislature would simply grant copyright ownership directly to the entity that deploys the AI rather than go through the extra step of vesting the AI with legal personhood to satisfy the requirements of the WMFH doctrine. Regardless, even if AI is not directly applied, the WMFH doctrine is still relevant for the purpose of considering whether AI-generated works can be copyrighted: it demonstrates that an entity can be considered an author without contributing expression, as long as that entity is providing some form of direction or economic investment in the creation process [27]. When used as an analogy, WMFH doctrine establishes that copyright can be grounded in economic relationships. In the context of AI-generated works, this could mean that the copyright would be attributed to the owner or the developer of the autonomous AI system, even if the owner or developer did not directly contribute expression to the work. Therefore, whether applied directly or as an analogy, WMFH provides a viable legal path for AI-generated works to be copyrightable; it is plausible that works generated autonomously by strong AI could one day be eligible for copyright protection.

V. SHOULD AI-GENERATED WORK BE COPYRIGHTABLE?

Even if AI could qualify to create copyrightable works, that does not mean that AI-generated works should be granted copyright protection. The normative questions remain: what is copyright meant to protect, and whom is it designed to serve?

V.1 Incentive Theory

One important consideration in determining whether AI-generated work should be copyrightable is incentive theory, a central justification for copyright protection. According to incentive theory, copyright protection incentivizes creators to create by providing them with exclusive rights to their intellectual property. Copyright protection is thus a solution to the inherent underproduction problem associated with non-rivalrous and non-excludable goods [28]. The underproduction problem can be understood in terms of the economic theory on lighthouses as the quintessential public good: a lighthouse that provides light to paying boats will also provide light to non-paying boats. The lighthouse’s light is a non-rivalrous good because one boat’s use of the light as a guide to shore would not diminish the ability of another boat to use it. The light is also a non-excludable good because it would be difficult to prevent the light from being used by non-paying boats. When people can easily access a good without paying, creators have less financial incentive to innovate and create those goods. By making works excludable, copyright protection ensures that creators can control who can access and use their work.

Copyright protection for AI-generated work cuts both ways when considering incentive theory. On the one hand, by granting copyright protection to AI-generated works, developers and corporations may be incentivized to invest more time and money into developing AI systems. On the other hand, granting copyright protection to AI-generated works might disincentivize human creators as their labor may be devalued in a market saturated with AI-generated content. Granting copyright protection to AI-generated works would, in a way, recreate the same underproduction problem that copyright was designed to solve.

V.2 Market Monopolization

A second consideration in determining whether AI-generated work should be copyrightable is the potential for corporations to use AI to mass-produce creative works and secure copyrights for those works. This could lead to a select few dominant tech companies monopolizing creative markets and crowding out human creators. This would be further worsened if the creators or owners of AI systems are granted copyright of the outputs of their AI regardless of who prompts the outputs. In this way, extending copyright to AI-generated works risks undermining the original purpose of copyright: to encourage individual authorship and innovation.

V.3 Limited Liability

A third consideration in determining whether AI-generated work should be copyrightable is the question of who would be held liable in the case that AI were to generate harmful outputs. Limited liability is a legal concept that stems from corporate personhood: when corporations are treated as separate legal entities from their owners, the owners are shielded from direct responsibility for corporate actions [29]. Limited liability protects shareholders or members from being held personally liable for debts incurred by a business entity [30].

If extending copyright to AI-generated works entails granting AI legal personhood, it could also introduce a potentially troubling version of limited liability: if developers are treated as legally separate from their AI systems, they may be able to limit their responsibility not only for financial liabilities, but also for harmful outputs produced by the AI. Developers would thus benefit from their AI systems without bearing the full legal consequences of the contents of their outputs. Since AI cannot meaningfully bear legal consequences, this could lead to a system that deprioritizes accountability and incentivizes developers and companies to pursue riskier projects.

Ultimately, even if AI-generated works could qualify for copyright, the cons would outweigh the pros. Accelerated technological advancement would come at the expense of human creativity, fair creative competition, and accountability for harm. As copyright law evolves in response to these new technologies, it is important that it continues to prioritize human authorship and safety.

VI. CONCLUSION

As AI technologies continue to advance, the legal and ethical questions surrounding copyright authorship will only become more pressing. As demonstrated by the rulings in the Thaler v. Perlmutter case, under current U.S. copyright law, purely AI-generated works are not eligible for copyright protection. However, at the end of the day, the language of the Constitution is ambiguous enough to accommodate new interpretations. In the face of this possibility, it is important to consider whether extending copyright protection to AI-generated works aligns with the original intent of copyright: to “promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts” [31]. Given that extending protection would devalue and disincentivize human creators, compromise fair creative competition, and potentially even encourage unaccountable risk, purely AI-generated works should not be eligible for copyright protection.

References

- Thaler v. Perlmutter, 130 F.4th 1039, 1041 (D.C. Cir. 2025).

- The Library of Congress, United States Copyright Office, Compendium of U.S. Copyright Office Practices, 3rd ed. (Washington DC: U.S. Copyright Office, 2021), § 101, https://www.copyright.gov/comp3/docs/compendium.pdf.

- 17 U.S.C. § 102(a).

- 17 U.S.C. § 106.

- United States Copyright Office, “Overview,” copyright.gov, accessed May 12, 2025, https://www.copyright.gov/about/.

- U.S. Const. art. I, § 8, cl. 8.

- 17 U.S.C. § 101.

- Thaler v. Perlmutter, 687 F. Supp. 3d 140, 144 (D.D.C. 2023).

- United States Copyright Office, Re: Second Request for Reconsideration for Refusal to Register A Recent Entrance to Paradise, Correspondence ID 1-3ZPC6C3; SR # 1-7100387071. Washington, D.C.: Copyright Office, 2022. Letter, https://www.copyright.gov/rulings-filings/review-board/docs/a-recent-entrance-to-paradise.pdf.

- Thaler v. Perlmutter, 687 F. Supp. 3d 140, 146 (D.D.C. 2023).

- Burrow-Giles Lithographic Company v. Sarony, 111 U.S. 53, 58 (1884).

- Thaler v. Perlmutter, 687 F. Supp. 3d 140, 147 (D.D.C. 2023).

- Id.

- Id. at 150.

- Thaler v. Perlmutter, 130 F.4th 1039, 1052 (D.C. Cir. 2025).

- Thaler v. Perlmutter, 130 F.4th 1039, 1041 (D.C. Cir. 2025).

- Id. at 1049.

- Library of Congress, “Copyright Registration Guidance: Works Containing Material Generated by Artificial Intelligence,” Federal Register 88, no. 51 (March 16, 2023): 16190-16194. https://www.govinfo.gov/app/details/FR-2023-03-16/2023-05321.

- If Thaler files a petition for a writ of certiorari, the case could be reviewed by the U.S. Supreme Court. At the time of writing, no petition has been filed.

- Feist Publications, Inc. v. Rural Tel. Serv. Co., 499 U.S. 340, 341 (1991).

- Id. at 346. In Feist, a telephone directory that was required to be published by law and merely listed names, phone numbers, and town names in a manner that lacked originality was found to be not copyrightable.

- 17 U.S.C. § 101.

- Thaler v. Perlmutter, 687 F. Supp. 3d 140, 150 n.3 (D.D.C. 2023).

- “legal person,” Legal Information Institute, Cornell University, June 2023. https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/legal_person.

- Reyes, Carla, “Autonomous Corporate Personhood,” Washington Law Review 96, no. 4 (2021): 1491.

- Halsey, Linda, “Article: Why Idaho Should Revisit Its Prohibition of Personhood for AI,” Idaho Law Review 60 (2021): 68.

- 17 U.S.C. § 101.

- Golger, Brian, “Comment: Copyright in the Artificially Intelligent Author: A Constitutional Approach Using Philip Bobbitt’s Modalities of Interpretation,” University of Pennsylvania Journal of Constitutional Law 22 (2020): 880.

- David Millon, “The Ambiguous Significance of Corporate Personhood,” 2 Stan. Agora: Online J. Legal Persp. 39 (2001): 45.

- “Limited liability,” Legal Information Institute, Cornell University, June 2023. https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/limited_liability.

- U.S. Const. art. I, § 8, cl. 8.